The birth of the father.

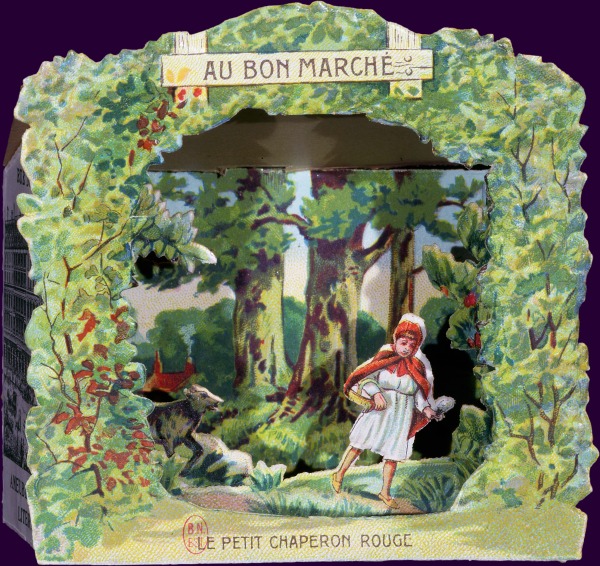

It is The Ladies' Paradise, as Zola rechristened the more prosaic Bon Marché: a concentrate of the metropolis, just as the metropolis is a concentrate of the world. In the new space invented by it - the shop-window, where inside and outside are no longer differentiated - the commodities of the bourgeois century finally appear in their full glory...

...What a delightful paradox: a bourgeois institution, which perverts bourgeois morality, impelling a Professor from the University of Lyon to demand 'police measures, to prevent minors under eighteen, of either sex, from entering' - and even 'a gendarme close to every sales counter.' The inventors of consumer society were too clever, and ended going too far. This overkill of consumers must be remedied, by situating them - like Faust in the witches' kitchen - at the right distance from the magic mirror of the commodity. Not too far, so that distance cools their minds and may induce them to pass on without buying; but not too close either, so as to avoid scandals.

Franco Moretti, Modern Epic (via Chabert)

This poisoned gift of bourgeois culture had, within it, its own remedy:

Aristide Boucicaut, father of the Bon Marché.

...bourgeois culture in France was divided within itself, not so much between upper and lower bourgeoisie or the forces of progress and stagnation as between two sets of values and attitudes, one that drove it to create what the other was bound to regret. If it was a culture that gave way to rationalized structures like the department store, it was also a culture that remained impregnated with strong relationships between family and business and one that believed in individual achievement. If it was a culture that carried within it a materialistic streak leading inexorably to a cult of consumption, it was also a culture whose sense of distinctions, self-restraints, and standards saw in much of this reason for fear and for horror.

The department store brought out bourgeois schizophrenia....

...The significance of the Bon Marché and its history lay in its ability to resove this dilemma by redifining traditions to fit new social contexts, thereby reconciling the divergent strains within bourgeois culture. Internally, a new idea of the firm integrated family values with bureacratic realities. White-collar workers wree fitted into bureacratic work slots in ways that retained their loyalty to the firm and its goals and assured their identity with middle-class values. Managers were formed who did not contradict the family origins of entrepreneurial firms. A sense of an internal House community was associated with the workings of a dynamic and rationalized system. All this was accomplished through innovative uses of paternalistic traditions, uses that eased owners, and later managers, into new business roles that they would now have to occupy. The method was systematic but almost elegant in its simplicity. Household relationships were redesigned to build an organizational work force of managers and clerks. The new relationships in turn provided the basis for the reorientation of the family firm. One followed from another just as tradition became imbedded in change. Externally, the projection of an image where the old and the new were inextricably intertwined—again based largely on imaginative uses of Bon Marché paternalism—revealed that one set of values need not disappear with the triumph of the other.

Michael Miller, The Bon Marché: Bourgeois Culture and the Department Store, 1869-1920.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home